DPHE: Protecting Server Privacy in CKKS-based Protocols

- Written by Jinyeong Seo (Seoul National University)

- Based on https://ia.cr/2025/382 (Asiacrypt 2025)

TL;DR: We investigate methods for protecting server privacy in CKKS-based protocols. Unlike exact homomorphic encryption schemes, formally defining security notions for the server is challenging in CKKS-based protocols due to the approximate nature of CKKS. We address this by introducing a new security notion called Differentially Private Homomorphic Encryption, which is motivated by differential privacy. Based on this notion, we construct a general compiler that transforms CKKS-based protocols into DPHE protocols. We also present the first zero-knowledge argument of knowledge for CKKS ciphertexts to protect server privacy against malicious clients.

1.Introduction

In recent years, CKKS has become a popular choice for building privacy-preserving machine learning (PPML) protocols. The primary reason for its popularity is its support for efficient real and complex arithmetic. This feature enables straightforward design of machine learning as a service (MLaaS) protocols that protect user privacy. However, in most CKKS-based protocols, server privacy is not guaranteed. Specifically, a client may learn more than just the inference result, potentially gaining access to sensitive information such as model weights or training data. In delegated computation scenarios where the server’s model is public, such as in open-source large language models, this is not a major concern. However, in settings where the service provider aims to keep its model private—due to high training costs, risks of model jailbreaking, or legal and regulatory issues involving sensitive data such as health or legal information—protecting server privacy becomes critical. Thus, in this paper, we aim to address the following question in CKKS-based protocols.

How can we protect the server’s privacy in CKKS-based MLaaS protocols?

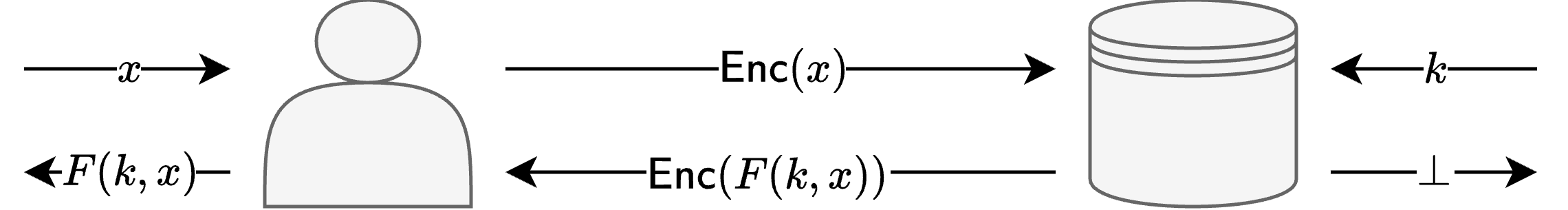

2. Server Privacy in Homomorphic Evaluation Protocols

Circuit Privacy is Insufficient

For other homomorphic encryption (HE)-based protocols, protecting server privacy has been studied in the context of standard two-party computation (2PC) protocol security, which is often referred to as circuit privacy. The circuit privacy framework is suitable for two-party cryptographic protocols, such as oblivious pseudo-random function (OPRF) protocols 1, where the output reveals no information at all about the server’s input. However, for encrypted MLaaS protocols, where the output often contains too much information about the server’s input, circuit privacy does not guarantee server privacy, as it does not prevent leakage from the output itself.

Estimating Privacy Leakage via Differential Privacy

To estimate server privacy leakage in CKKS-based MLaaS protocols, we utilize a differential privacy (DP)-based analysis beyond the circuit privacy framework. In plain MLaaS protocols, server privacy leakage is usually measured through the lens of differential privacy. In particular, it can be formalized through the notion of DP-prediction2, which is defined as follows.

Definition (DP Prediction). Let $M : \Theta \times \mathcal{X} \rightarrow \mathcal{Y}$ be a random algorithm. We say that $M$ is an $\epsilon$-DP prediction algorithm if, for every $x \in \mathcal{X}$, the output $M(\theta, x)$ is $\epsilon$-DP with respect to $\theta \in \Theta$. In other words, for all adjacent $\theta, \theta’ \in \Theta$ and all PPT algorithms $\mathcal{A}$, the following holds.

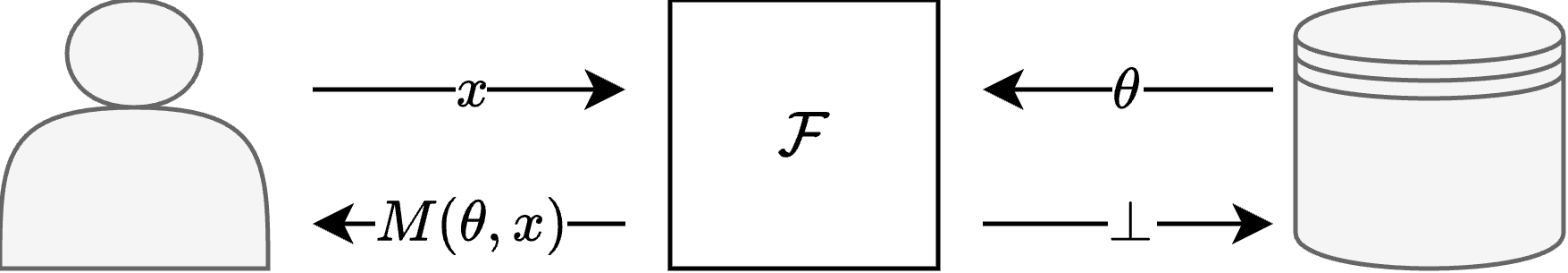

\[\Pr[ \mathcal{A}( M(\theta, x) ) = 1] \lesssim e^{\epsilon} \cdot \Pr[\mathcal{A}( M(\theta', x) ) = 1]\]The above definition models an MLaaS protocol where the client’s query is $x$ and the server’s model weight or training data is $\theta$. Then, the above definition essentially says that server privacy is maintained regardless of the client’s query. Then, we model the ideal functionality of encrypted MLaaS protocols as evaluating some DP-prediction algorithm $M$, which can be described as follows.

Ideal Functionality. The ideal functionality $\mathcal{F}$ for encrypted MLaaS protocols is defined as follows.

- Client’s input: $x \in \mathcal{X}$

- Server’s input: $\theta \in \Theta$

- Client’s output: $M(\theta, x)$

- Server’s output: $\bot$

Based on the above ideal functionality, we define the server’s privacy in encrypted MLaaS protocols as follows.

Definition (Server Privacy). Let $\Pi$ be a two-party protocol that implements the ideal functionality $\mathcal{F}$. We say $\Pi$ achieves server privacy with parameter $\epsilon$ if an execution of $\Pi$ is an $\epsilon$-DP prediction with respect to the server’s input $\theta$. In other words, the following holds for all PPT adversaries $\mathcal{A}$ that manipulate the client, and all PPT environments $\mathcal{Z}$.

\[\Pr[\mathsf{Exec}[\Pi_{\theta}, \mathcal{A}, \mathcal{Z}] = 1] \lesssim e^{\epsilon} \cdot \Pr[\mathsf{Exec}[\Pi_{\theta'}, \mathcal{A}, \mathcal{Z}] = 1]\]The above definition can be interpreted as a natural extension of DP-prediction in a two-party computation scenario. In other words, the above definition ensures that the protocol $\Pi$ protects the server’s input $\theta$ in terms of differential privacy against all adversarial clients’ inputs $x$.

Circuit Privacy implies Server Privacy

One interesting corollary is that circuit privacy remains meaningful within our new definition of server privacy. To present more details, we recall the definition of circuit privacy below.

Definition (Circuit Privacy). Let $\Pi$ be a two-party protocol that implements the ideal functionality $\mathcal{F}$. We say $\Pi$ achieves circuit privacy if there exists a PPT simulator $\mathcal{S}$ such that the following holds for all PPT adversaries $\mathcal{A}$ that manipulate the client, and all PPT environments $\mathcal{Z}$.

\[\Pr[\mathsf{Exec}[\Pi_{\theta}, \mathcal{A}, \mathcal{Z}] = 1] \approx \Pr[\mathsf{Exec}[\mathcal{F}_{\theta}, \mathcal{S}, \mathcal{Z}] = 1]\]Then, we can derive the following result.

Theorem (Circuit Privacy). Let $\Pi$ be a two-party protocol that implements the ideal functionality $\mathcal{F}$. Suppose the target model $M$ in $\mathcal{F}$ is an $\epsilon$-DP prediction and $\Pi$ achieves circuit privacy, then $\Pi$ achieves server privacy with parameter $\epsilon$.

The above theorem says that if the target model $M$ is a DP-prediction algorithm and $\Pi$ achieves circuit privacy, then $\Pi$ guarantees server privacy. Thus, we can conclude that achieving circuit privacy is still meaningful in the context of encrypted MLaaS protocols if the target models are set to DP prediction algorithms.

3. Differentially Private Homomrphic Evaluation

Motivation

Within our new server privacy notion, the problem of achieving server privacy seems to essentially boil down to achieving circuit privacy, which naturally leads to the following questions in the case of CKKS-based protocols.

Can we achieve circuit privacy in CKKS-based protocols?

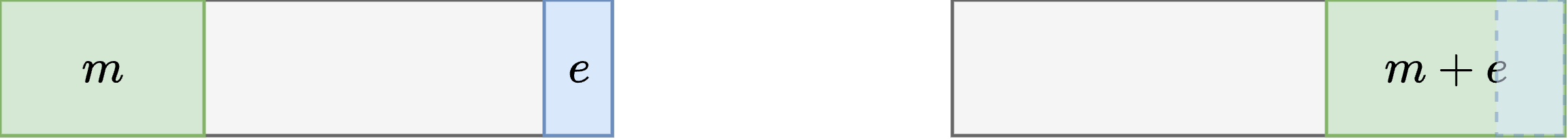

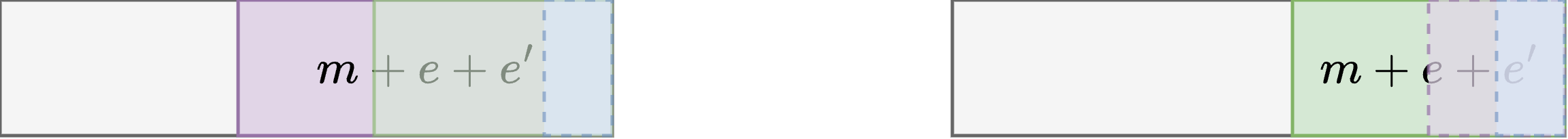

The answer to the above question is No in general due to the peculiar structure of CKKS ciphertexts. To demonstrate the reasons, we first compare the ciphertext structure of CKKS with that of other exact HE schemes, such as BFV. In a BFV ciphertext, a noise term $e$ and a plaintext $m$ are strictly separated, so they do not interfere with each other unless $e$ exceeds the decryption bound. However, in a CKKS ciphertext, the noise $e$ and the plaintext $m$ exist in a fused state $m + e$, and they cannot be separated once encryption is performed. Thus, the size of the noise affects the precision of the plaintext after decryption, as they interfere with each other.

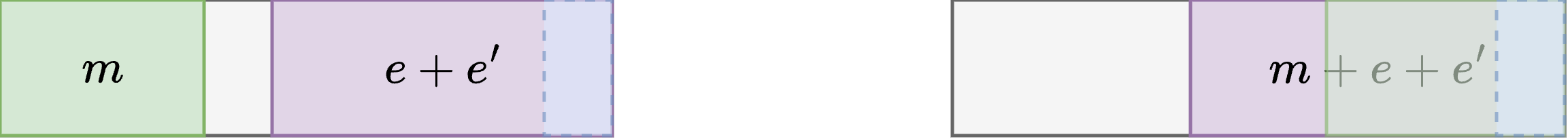

To achieve circuit privacy, one frequently utilized technique is noise flooding, which introduces additional noise $e’$ to erase any circuit information remaining in the noise part $e$. To achieve the indistinguishability notion in circuit privacy, the size of $e’$ is set to be exponentially larger than $e$. This is acceptable for BFV ciphertexts if $e + e’$ remains below the decryption bound, as the additional noise does not alter the value $m$ of the plaintext. However, for CKKS ciphertexts, excessive noise corrupts the plaintext value because they are fused. To be precise, performing noise flooding results in a decryption result of $m + e + e’$. If $e’ \gg m$, then the decryption result becomes entirely unusable for the client, even though circuit privacy is achieved.

Definition

We observe that the main difficulty in achieving circuit privacy arises from the computational indistinguishability requirement between the ideal functionality and the real protocol execution. However, if our final goal is to achieve server privacy, which is estimated in terms of differential privacy, requiring computational indistinguishability can be an overkill. Thus, we define the concept of differentially private homomorphic evaluation3 (DPHE) as follows to resolve this issue.

Definition (DPHE). Let $\Pi$ be a homomorphic evaluation protocol that implements ideal functionality $\mathcal{F}$. We say $\Pi$ is an $\epsilon$-DPHE protocol for $F$ if there exists a PPT simulator $\mathcal{S}$ such that the following holds for all PPT adversaries $\mathcal{A}$ that manipulate the client, and all PPT environments $\mathcal{Z}$.

\[\Pr[\mathsf{Exec}[\Pi_{\theta}, \mathcal{A}, \mathcal{Z}] = 1] \lesssim e^{\epsilon} \cdot \Pr[\mathsf{Exec}[\mathcal{F}_{\theta}, \mathcal{S}, \mathcal{Z}] = 1]\] \[\Pr[\mathsf{Exec}[\mathcal{F}_{\theta}, \mathcal{S}, \mathcal{Z}] = 1] \lesssim e^{\epsilon} \cdot \Pr[\mathsf{Exec}[\Pi_{\theta}, \mathcal{A}, \mathcal{Z}] = 1]\]The above definition can be viewed as a relaxation of the indistinguishability notion in circuit privacy into something analogous to differential privacy. Once a protocol satisfies the DPHE property, we can derive the following result.

Theorem (DPHE). Let $\Pi$ be a two-party protocol that implements the ideal functionality $\mathcal{F}$. Suppose the target model $M$ in $\mathcal{F}$ is an $\epsilon$-DP prediction and $\Pi$ achieves $\epsilon’$-DPHE property, then $\Pi$ achieves server privacy with parameter $\epsilon+2\epsilon’$.

Therefore, we can conclude that achieving the DPHE property is sufficient for server privacy instead of achieving circuit privacy.

Instantiation

Once we verify that the DPHE property is sufficient, it naturally leads to the following next questions.

Can we achieve the DPHE property in CKKS-based protocols?

The answer is Yes, and we show how to instantiate a DPHE protocol by compiling existing CKKS-based protocols. The core idea is to utilize the Laplace mechanism4 to achieve differential privacy. Suppose the ciphertext space is \(R_q = \mathbb{Z}_q[X]/(X^N + 1)\) and security parameter is given as $\mathbf{1}^{\lambda}$. We recall that to achieve circuit privacy, the noise flooding method introduces additional noise $e’$ whose norm is $O(2^{\lambda} \cdot B_e)$, where $B_e$ is an upper bound of the norm $\Vert e \Vert_{\infty}$ of the initial noise $e$. However, to achieve the DPHE property, it suffices to add additional noise $e’$ whose norm is $O(N B_e)$, which is significantly smaller than that of noise flooding.

The detailed procedure is as follows. Suppose a protocol $\Pi$ aims at evaluating a DP mechanism $M$ on the client’s encrypted input $\mathsf{ct}_{in} = \mathsf{Enc}(x)$. Let $\tau > 0$ be an $L^1$-norm bound for the noise when evaluating $M$ in CKKS evaluation algorithms for $\theta \in \Theta$ and $x \in \mathcal{X}$. Then, the compilation is achieved as follows.

- $(c_0, c_1) \gets \mathsf{Eval} \big( M(\theta, \cdot), \mathsf{ct}_{in} \big) \pmod{q}$

- $(c’_0, c’_1) \gets (c_0, c_1) + (\lceil t \rfloor, 0) \pmod{q}$ for $t \gets \mathsf{Lap}(N \tau / \epsilon’)^N$

- \(\mathsf{ct}_{out} \gets q' \cdot (c'_0, c'_1) + \mathsf{Enc}_{\mathsf{pk}}(0) \pmod{qq'}\)

The second step is for achieving the differential privacy property on the client’s output plaintext, and the third step is to remove any remaining information in the ciphertext components by adding an encryption of zero. As a corollary, our compiler results in the following result.

Corollary (DPHE Compiler). Let $\mathcal{F}$ be the ideal functionality for homomorphic evaluation of an $\epsilon$-DP prediction algorithm $M$. Then, the DPHE compiler produces an $\epsilon’$-DPHE protocol $\Pi$ that implements $\mathcal{F}$, and $\Pi$ achieves server privacy with parameter. $\epsilon + 2\epsilon’$

Therefore, by relaxing the security notion for homomorphic evaluation protocols, we succeed in achieving server privacy in CKKS-based protocols.

4. ZKAoK for CKKS Ciphertexts

Our DPHE compiler is based on the assumption that the input ciphertext is well-formed and the input message lies in the domain $\mathcal{X}$. However, for malicious clients, there is no guarantee that the input ciphertext satisfies these conditions. Thus, for the server to verify these conditions without compromising the client’s privacy, we need a zero-knowledge argument of knowledge (ZKAoK) for CKKS ciphertexts.

However, designing ZKAoK for CKKS is nontrivial, and there have been no previous attempts for it. The main difficulty arises from the lack of techniques for verifying the validity of the message, i.e., $\vec{x} \in \mathcal{X} \subseteq \mathbb{R}^N$. To be precise, when encrypting a message $\vec{x} \in \mathbb{R}^N$, it is encoded into a polynomial $m(X) \in R_q$ that lies in the ciphertext space $R_q = \mathbb{Z}_q[X]/(X^N + 1)$. Current ZKAoK for HE ciphertexts5 only support verification of arithmetic relations defined over $R_q$, whereas we need to verify the condition $x \in \mathcal{X}$, which is defined over $\mathbb{R}^N$.

Solution

We address this issue by delegating the encoding procedure to the server, described below.

- For an input message $\vec{x} := (x_0, \dots, x_{N-1}) \in \mathbb{R}^N$, the client generates a plaintext $m’(X) \in R_q$ with scaled coefficient packing as follows.

- $m’(X) = \lceil \Delta x_0 \rceil + \lceil \Delta x_1 \rceil X + \cdots + \lceil \Delta x_{N-1} \rceil X^{N-1}$

- The client generates a ciphertext $\mathsf{ct}’ = (a’, b’) \in R_q^2$ from $m’(X)$ and proves the following relations hold through ZKAoK for HE ciphertexts.

- $b’ - a’ s = m’ + e’ \pmod{q}$

- $\Vert s \Vert_{\infty} \le B_s$ and $\Vert e’ \Vert_{\infty} \le B_e$

- $\mathsf{Coeff}(m’) \in \lceil \Delta \mathcal{X} \rceil \subseteq \mathbb{Z}_q^N$

- The server verifies the ZKAoK for the ciphertext $\mathsf{ct}’$, and obtains the actual input ciphertext $\mathsf{ct}$ as follows.

- $\mathsf{ct} \gets \mathsf{CoeffToSlot}(\mathsf{ct}’)$

The scaled coefficient packing in the first step allows a client to generate a ZKAoK for verifying the input domain in $R_q$. After the server verifies this ZKAoK, it can generate an input ciphertext whose slot values correspond to these coefficient values by applying the coeff-to-slot operation. As a result, the server can ensure that input ciphertexts are well-formed, i.e., the input messages lie within the input domain.

Benchmark

With the above technique, we instantiate the first ZKAoK for CKKS ciphertexts6 that can verify the input domain. Specifically, we construct the ZKAoK for CKKS, which proves that input messages of ciphertexts lie in $[-1, 1]^N$, together with well-formedness of public keys, including encryption, relinearization, rotation key, and conjugation key. In the following table, we provide the concrete benchmark results, where $k$ denotes the number of ciphertexts, $\Delta$ denotes the scaling factor, PK Size denotes the total size of public keys, and CT Size denotes the total size of ciphertexts. The performance is measured on an Intel Xeon Platinum 8268 CPU with a single thread.

| $k$ | $ \log\Delta $ | PK Size | CT Size | Proof Size | Prover Time (s) | Verifier Time (s) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 2 | 16 | 39.5 MB | 1.57 MB | 17.9 MB | 324.35 | 50.88 |

| 4 | 16 | 39.5 MB | 3.14 MB | 18.9 MB | 365.46 | 56.08 |

| 8 | 16 | 39.5 MB | 6.28 MB | 21.0 MB | 442.86 | 67.13 |

| 2 | 32 | 39.5 MB | 1.57 MB | 18.7 MB | 356.90 | 54.65 |

| 4 | 32 | 39.5 MB | 3.14 MB | 20.4 MB | 425.26 | 64.33 |

| 8 | 32 | 39.5 MB | 6.28 MB | 24.0 MB | 561.28 | 83.63 |

5. Conclusion

In summary, we examine the server privacy issues in CKKS-based protocols, particularly for encrypted MLaaS protocols. The key takeaways are as follows.

- We formalize the security notion for server privacy based on differential privacy.

- We achieve server privacy for CKKS without noise flooding.

- We construct the first zero-knowledge argument of knowledge for CKKS to handle malicious clients.

References

-

Martin R. Albrecht, Alex Davidson, Amit Deo, and Daniel Gardham. “Crypto Dark Matter on the Torus: Oblivious PRFs from shallow PRFs and TFHE.” Eurocrypt 2024. ↩

-

Cynthia Dwork and Vitaly Feldman. “Privacy-preserving prediction.” COLT 2018. ↩

-

Intak Hwang, Seonhong Min, Jinyeong Seo, and Yongsoo Song. “On the security and privacy of CKKS-based homomorphic evaluation protocols.” Asiacrypt 2025. ↩

-

Cynthia Dwork, Frank McSherry, Kobbi Nissim, and Adam Smith. “Calibrating noise to sensitivity in private data analysis.” TCC 2006. ↩

-

Intak Hwang, Hyeonbum Lee, Jinyeong Seo, and Yongsoo Song. “Practical zero-knowledge PIOP for maliciously secure multiparty homomorphic encryption.” ACM CCS 2025. ↩