Bootstrapping Discrete Data with CKKS

- Written by Jaehyung Kim (Stanford University)

- Based on https://ia.cr/2024/1637 (Asiacrypt 2024)

TL;DR: Recently, a new paradigm called discrete CKKS, which picks the best aspects of CKKS and other exact schemes has been suggested. To be more specific, it uses CKKS (a.k.a. the approximate homomorphic scheme) to compute over discrete data. In this article, we discuss the recent discrete bootstrapping in BKSS24 specifically designed for discrete CKKS.

Discrete CKKS

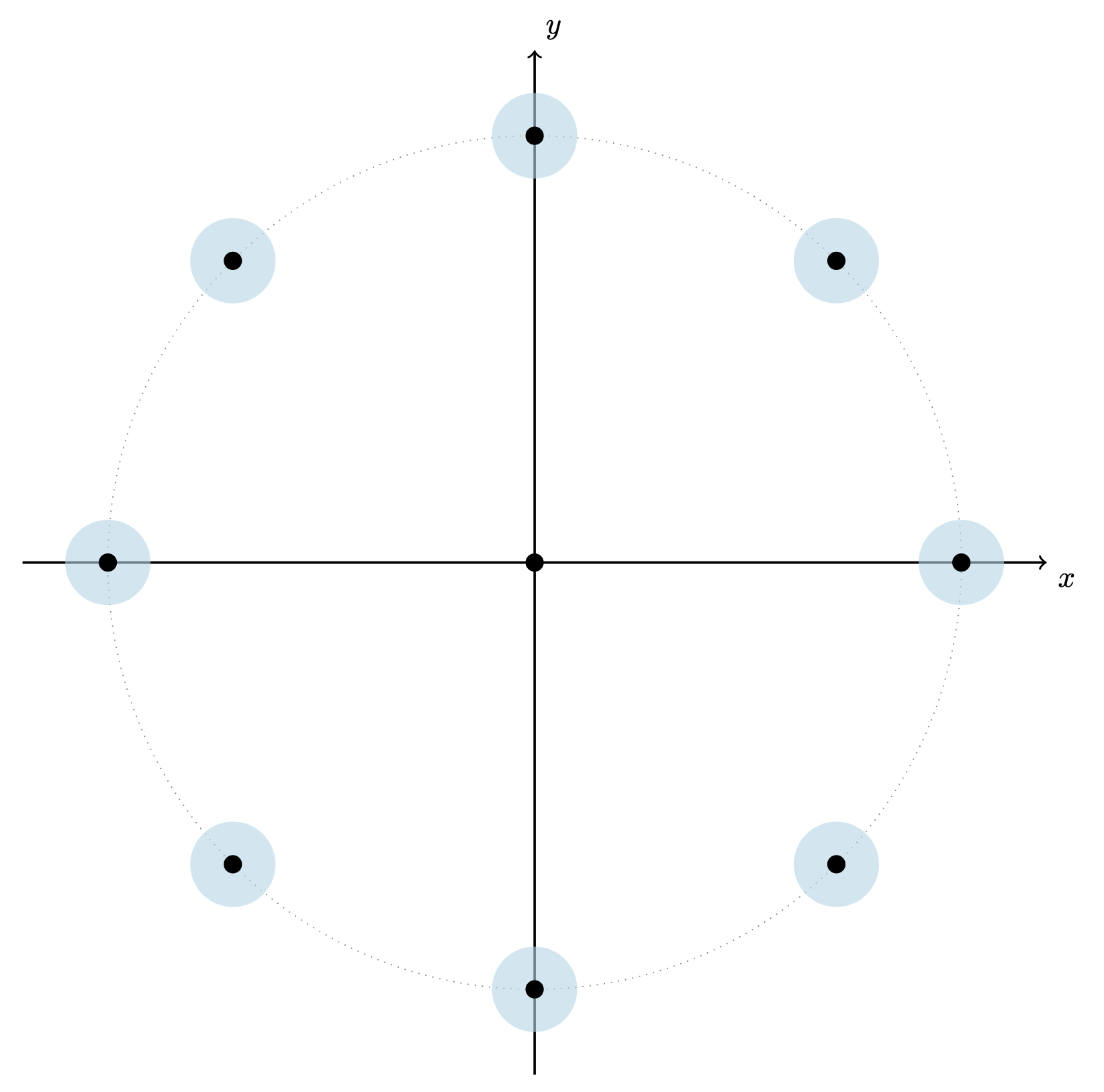

Recall that CKKS is defined over the complex plane $\mathbb{C}$. We consider a finite discrete subset $U$ of $\mathbb{C}$ such as \(\mathbb{Z}_t = \{0, 1, \ldots, t-1\}\) for some $t \in \mathbb{Z}$ or a set of complex $t$-th root of unity $\mu_t = {exp(2 \pi i m / t)}_{0 \leq m < t}$. Instead of using the entire $\mathbb{C}$ as the message space, we may use the subset $U$ as long as $U$ is closed under some arithmetic operations (e.g. $+$, $\times$). For instance, if $U = \mu_t$, we may instantiate addition over $\mu_t$ via multiplication over $\mathbb{C}$. The picuture below describes a set $\mu_8$, where the lightblue circles denote that CKKS allows some errors to the representations of each root of unity.

Using a restricted message space $U$ gives us two powerful capabilities. One is interpolation which allows us to compute arbitrary functions. Recall that addition and multiplication over the entire complex plane only support approximations which can only evaluate certain (semi-)continuous functions. On the other hand, interpolation over finite number of points can evaluate any function. For instance, the Lagrange interpolation allows us to send $k+1$ distinct points on the complex plane to arbitrary $k+1$ points on the complex plane via a degree $k$ polynomial. As CKKS supports addition and multiplication over integers, it can evaluate any complex coefficient polynomials.

The other capability is message-error separation which allows one to distinguish error from the message. For example, let $U = \mathbb{Z}_8$ and one of the entries of the decryption of a ciphertext be 3.97. If the ciphertext were a usual CKKS ciphertext encrypting any real number, then we would not be able figure out what the actual message is (e.g. 3.95, 3.98, … can be candidates). However, since we know that the error is significantly smaller than the gaps between the elements of $U$, we can recover the original message, i.e. $4 = Round(3.97)$.

As computations proceed, the error continously grows. To reduce it, we use cleaning polynomials with vanishing derivatives. For instance, the bit cleaning polynomial $h_1(x) = 3x^2-2x^3$ satisfies $h_1(0)=0$, $h_1(1)=1$, and $h_1’(0)=h_1’(1)=0$, sending complex numbers close to $0$, $1$ to numbers even closer to $0$, $1$, respectively. In this regard, the cleaning homomorphically reduces the error, allowing infinite number of operations without a contamination of the messages by the errors.

CKKS bootstrapping reminders

When multiplying two CKKS ciphertexts with a scaling factor $\Delta$, the resulting ciphertext has a scaling factor $\Delta^2$. In order to reduce the scaling factor back to $\Delta$, we rescale by $q \approx \Delta$ for some $q$ that divides the ciphertext modulus. This is a necessary step that prevents the scaling factors from growing exponentially, but it consumes some ciphertext modulus per every multiplication. The CKKS bootstrapping is a homomorphic operation that recovers the ciphertext modulus.

The key idea of the CKKS bootstrapping is very simple. If we raise the ciphertext modulus by simply embedding a small modulus $q_0$ into a larger modulus $Q$, a small multiple of $q_0$ is added to the plaintext. In other words, if the initial ciphertext encrypts a plaintext $m$, then the resulting ciphertext encrypts $m + q_0 \cdot I$ for some small integral $I$. In order to remove the $I$ term, we regard the new scaling factor as $q_0$ and homomorphically evaluate a modulo-$1$ function.

A common approach for CKKS bootstrapping is to use trigonometric functions to approximate modular reduction. As long as $m$ is sufficiently smaller than $q_0$, the (scaled) trigonometric sine function $sin(2 \pi x) / (2 \pi)$ successfully removes $I$ while preserving $m$, as $sin(x) \approx x$ for small $x$. A sine function with a small number of periods can be efficiently approximated by well-known techniques such as the minimax polynomial from the Remez algorithm(s).

Discrete bootstrapping

Although we can use any CKKS bootstrapping as a black box to bootstrap a discrete CKKS ciphertext, it is an interesting question whether there exists a more efficient, dedicated bootstrapping for discrete encoding. It turns out that there exists such a variant which not only efficiently bootstraps discrete data but also evaluates an arbitrary function as in functional/programmable bootstrapping in the context of CGGI/DM.

We first recall the scheme conversion in Chimera which evaluates a complex exponential function to convert a low-level RLWE ciphertext into a high-level CKKS ciphertext. That is, given a modulus-raised ciphertext encrypting $m + q_0 \cdot I$, we evaluate $x \mapsto exp(2 \pi i x)$ which gives us $exp(2 \pi i m /q_0)$ while removing the $I$ part. In the discrete bootstrapping framework, we use this as a subroutine to achieve bootstrapping. An interesting observation is that the complex exponential function sends the equispaced points on the real line (i.e. $\mathbb{Z}_t$) to the equispaced points on the unit circle (i.e. $\mu_t$).

Although any finite set of points provides interpolation, the set of complex roots of unity is a good candidate because its interpolation is numerically more stable than other alternatives, as illustrated in CKKL24. Given an arbitrary function from $\mathbb{Z}_t$ to $\mathbb{Z}_t$, we may translate such function as an interpolation from complex $t$-th roots of unity to $\mathbb{Z}_t$, allowing us to evaluate arbitrary look-up tables.

The combination of the complex exponential in the first step and the interpolation in the second step gives us a CKKS bootstrapping for discrete data (i.e. raising modulus) plus evaluating an arbitrary function $: \mathbb{Z}_t \rightarrow \mathbb{Z}_t$.

Implications

The discrete CKKS framework has been introduced in BLEACH, and the discrete bootstrapping in BKSS24 further improves the framework by using bootstrapping in a non-black-box manner. In particular, the discrete bootstrapping suggests that one had better integrate bootstrapping and look-up table evaluation, and the rest of the moduli can be reserved for arithmetic operations (i.e. addition and multiplication) if needed.

In terms of functionality, the discrete variant of CKKS extends the capability of CKKS to support arbitrary, possibly discontinuous functions. Compared to other exact schemes, CKKS had been struggling to support such feature due to the nature of polynomial approximations. The discrete bootstrapping provides a perfect solution to the problem of arbitrary function evaluation, while achieving similar asymptotic complexity as other schemes. Recall that BGV/BFV evaluates an arbitrary function as an interpolation over non-zero characeteristic fields, whose efficiency should be almost the same as interpolation over the complex plane.

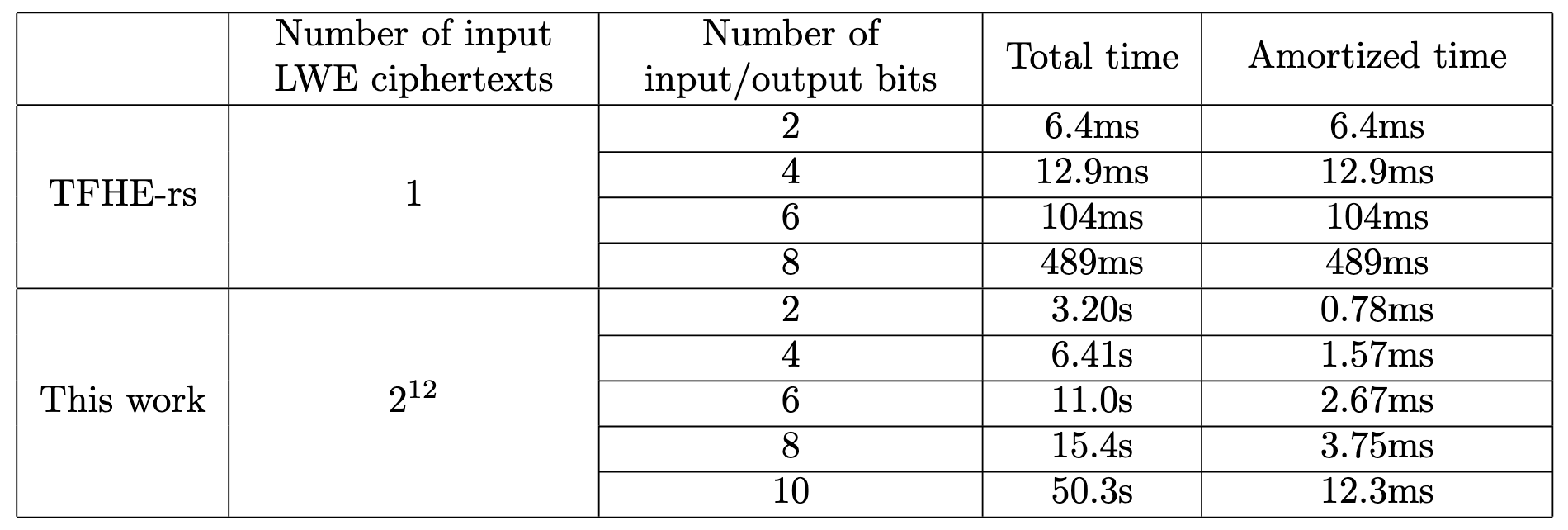

In terms of concrete efficiency, the discrete bootstrapping can be interpreted as a parallelization of CGGI/DM functional bootstrapping (i.e. bootstrapping an LWE ciphertext while evaluating an arbitrary function). The experiments in BKKS24 show that this new approach is several orders of magnitude faster than CGGI/DM in terms of throughput, as illustrated above. When there is a moderate number of ciphertexts (e.g. 100), the CKKS-style functional bootstrapping (i.e. discrete bootstrapping) already outperforms CGGI/DM. Note that the functional bootstrapping is a key building block of CGGI/DM that is used to evaluate any circuit. In this regard, the CKKS-style functional bootstrapping can be viewed as an accelerator for CGGI/DM computations.

In terms of security, discrete CKKS provides a solution for achieving advanced security notions (e.g. IND-CPA-D) without going through expensive (direct) noise flooding. Recall that the only known solution for CKKS to achieve such security notions is to work with high precision for the whole circuit evaluation and to add huge noise at the end. As discrete CKKS is an exact scheme, it can use the same strategies as other exact schemes, providing a much more efficient option.