Homomorphic Encryption for Data Science

- Written by Allon Adir, Ehud Aharoni, Nir Drucker, Ronen Levy, Hayim Shaul, Omri Soceanu (IBM Research, Israel)

- Based on https://link.springer.com/book/10.1007/978-3-031-65494-7 (Homomorphic Encryption for Data Science)

TL;DR: FHE has advanced significantly since its introduction fifteen years ago, yet it remains challenging to use efficiently. We examine methods addressing three of the major challenges faced by cryptographers and data scientists face when using FHE: data packing; polynomial approximations and data traversal.

More than a decade and a half has passed since the publication of Gentry’s original paper [1] about Fully Homomorphic Encryption (FHE). Since then, real progress has been made transforming FHE from a theoretical tool accessible only to a few into a practical solution with rapidly improving usability, performance, and abstraction. Still, the development of practical applications and data science models remains challenging for both cryptographers and data scientists. The three major challenges are outlined below and discussed in subsequent sections:

- Efficient data packing

- Accurate polynomial approximation of analytical functions

- Efficient data traversal

Efficient Data Packing and Tile Tensors

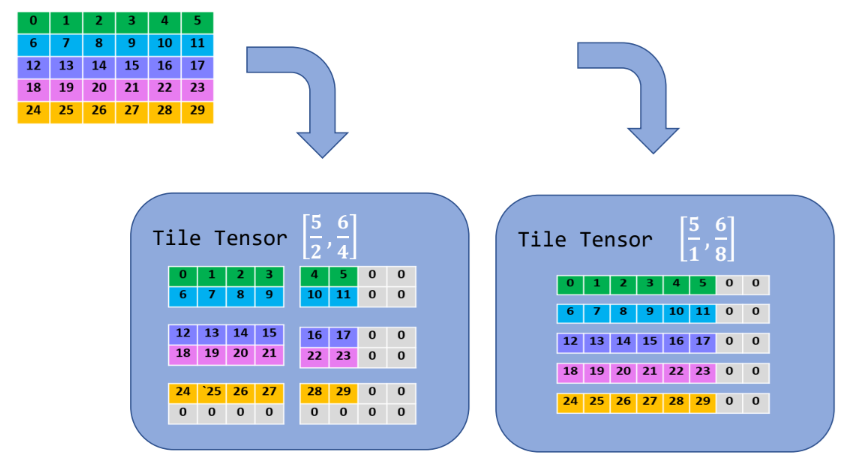

Several FHE schemes (e.g. BGV [2], BFV [3], CKKS [4]) encode a vector of plaintext values as polynomial coefficients and operate on it element-wise. Thus, encrypted data operations in many FHE schemes can be viewed as Single Instruction, Multiple Data (SIMD). Efficiently mapping complex data to these coefficients (or vector slots) is often a pain-point for developers. Tile tensors [5] simplify this packing process by defining the layout of tensors and their tiling using high-level “tile tensor shapes”. Tile tensors extend known packing approaches, allowing researchers to focus on the algorithms rather than on the ciphertext internals.

The idea behind tile tensors is to think of a ciphertext as a tile with a configurable shape and cover tensors with these tiles. This implies that the size of a tile equals the number of slots each ciphertext has. Changing the shape of the tiles changes how a tensor is packed into ciphertexts. For example, when covering a 2-dimensional matrix with a tile of shape 1x8 (assuming 8 slots in a ciphertext, for simplicity) we get row-based packing. With a tile of shape 8x1 we get column-based packing. Other shapes, such as 2x4 are also possible. See Figure 1 for an example.

Efficient and Accurate Polynomial Approximating

Another fundamental FHE challenge is function evaluation. Most FHE schemes support a handful of arithmetic primitives, such as element-wise addition, multiplication and vector rotation. Any operation beyond these primitives, e.g. division, comparison, not to mention complex neural network activation functions, requires some approximation. One can construct polynomials using only additions and multiplications, and then use them to approximate almost any function to a desired degree of accuracy. However, since the use of any primitive comes with an inherent computational cost, every operation should be assessed with scrutiny, to minimize the amount and type of operations to only those that are necessary to meet accuracy goals. The art here is twofold: devising polynomial approximations that are both accurate and of low-enough degree to achieve acceptable performance and representing and evaluating these polynomials in ways optimized for FHE. Efficient polynomial evaluation, packing tricks (that can be implemented with Tile Tensors), and circuit crafting are all essential.

Efficient Data Traversal

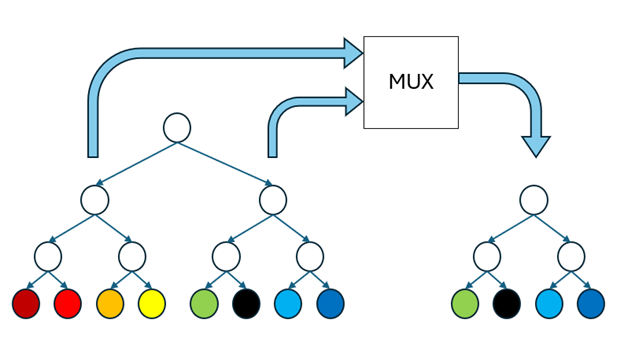

Since algorithms under FHE deal with encrypted messages they are unable to make any decision based on the encrypted input. This includes branching dynamically, i.e. take a path of the code depending on encrypted input. See for example [7]. Instead, algorithms need to evaluate all possible branches and multiplex (“select”) their output. Even a simple algorithm such as searching a binary tree becomes exponentially more expensive in FHE because it needs to traverse every path of the tree and not just a single one as in the cleartext case. Algorithms such as those needed in private database queries or machine learning (decision trees) suffer from this limitation and are not efficient under FHE.

Different methods have been proposed, among which is “Copy-and-Recurse” [8, 9]. Rather than branching, which is problematic under FHE, this method creates a copy (under FHE) of the branch that the algorithm needs to take and continues with this copy. Creating this copy requires a constant number of multiplications and additions for each node, but then any the number of expensive computations that are done at nodes (e.g., comparisons) is proportional to the cleartext algorithm.

A Book for the Practicing Cryptographer and Data Scientist

These challenges, alongside techniques and practical recipes to solve them, are important for algorithmic researchers attempting to utilize FHE. Each topic is explained further with concrete examples, code templates, and in-depth discussions in the book “Homomorphic Encryption for Data Science (HE4DS)” [10]. For cryptographers determined to bridge the theory-practice gap, and for data scientists eager to harness encrypted computation for real-world ML and analytics tasks, this text stands as an invitation: the road is still rugged, but the right tools and abstractions exist. The landscape of FHE is shifting from a field of delicate manual hacks to one supported by high-level libraries and reproducible patterns. Understanding these new abstractions will empower the next generation of privacy-preserving applications.

References

[1] Craig Gentry. “Fully Homomorphic Encryption Using Ideal Lattices.” Proceedings of the 41st Annual ACM Symposium on Theory of Computing (STOC 2009), pp. 169–178. ACM, 2009. DOI: 10.1145/1536414.1536440

[2] Zvika Brakerski, Craig Gentry, and Vinod Vaikuntanathan. “(Leveled) Fully Homomorphic Encryption without Bootstrapping.” Proceedings of the 3rd Innovations in Theoretical Computer Science Conference (ITCS 2012), pp. 309–325. ACM, 2012.

[3] J. Fan and F. Vercauteren. Somewhat practical fully homomorphic encryption. IACR Cryptol. ePrint Arch., 2012:144.

[4] Jung Hee Cheon, Andrey Kim, Miran Kim, and Yongsoo Song. “Homomorphic Encryption for Arithmetic of Approximate Numbers.” In Advances in Cryptology – ASIACRYPT 2017, Lecture Notes in Computer Science, vol. 10624, pp. 409–437. Springer, 2017.

[5] Ehud Aharoni, Allon Adir, Moran Baruch, Nir Drucker, Gilad Ezov, Ariel Farkash, Lev Greenberg, Ramy Masalha, Guy Moshkowich, Dov Murik, Hayim Shaul, and Omri Soceanu. “HeLayers: A Tile Tensors Framework for Large Neural Networks on Encrypted Data.” Proceedings on Privacy Enhancing Technologies (PoPETs), 2023(1): 325–342. DOI: 10.56553/popets-2023-0020

[6] Ehud Aharoni, Nir Drucker and Hayim Shaul, “Tutorial: Advanced HE packing methods with applications to ML”, ACM CCS 2022, https://research.ibm.com/haifa/dept/vst/tutorial_ccs2022.html.

[7] Sunchul Jung, “Convergent Evolution: Why Secure Homomorphic Encryption Will Resemble High-Performance GPU Computing”, https://ckks.org/blog/2025/convergent-evolution/#21-the-fhe-security-model-and-the-turing-barrier

[8] Eyal Kushnir, Guy Moshkowich, and Hayim Shaul. “Secure Range-Searching Using Copy-And-Recurse.” Proceedings on Privacy Enhancing Technologies (PoPETs), 2024(3).

[9] Eyal Kushnir and Hayim Shaul. “Improved Range Searching and Range Emptiness Under FHE Using Copy-And-Recurse.” Cryptology ePrint Archive, Paper 2025/751, 2025. Available at: https://eprint.iacr.org/2025/751

[10] Adir, A., Aharoni, E., Drucker, N., Levy, R., Shaul, H., and Soceanu, O. Homomorphic Encryption for Data Science (HE4DS). Springer Nature Switzerland, 2024. ISBN 9783031654947. Available at: https://link.springer.com/book/10.1007/978-3-031-65494-7